Telling stories has been an important function of art throughout history. After the Renaissance narrative slowly faded from main stream art in the west and it nearly disappeared in some movements during the height of modernism. This was the result of a political and philosophical environment that discouraged narrative. Even as the modernists were rooting out narrative from their work socialists were beginning to use it for propaganda. The kinds of stories being told and the people who were telling them in art were a good mirror of power and politics throughout history, but today narrative is both mirror and reality. Telling stories is one of the most important aspects of postmodern culture. The stories we tell often describe the world that we live in, but they also shape the world that we are going to live in. Narrative ceramics is not always considered to be cutting edge, but it is among the most important and defining modes of expression in postmodern clay. Through narrative artists encourage dialogue, share ideas, address morality, reveal desire, confront angst and define identity. As they do this they instigate change. Many contemporary artists borrow technique and content from historical narrative art and apply it to the contemporary context.

As Renaissance artists became more sophisticated in their ability to faithfully portray reality the complexity of their narrative devices devolved. It’s as though composition and perspective distracted them from the stories they were telling. Over time narrative faded slowly until it disappeared. Once abstraction moved away from representation it was no longer possible to tell stories. It’s true that some artists gave their pieces titles that alluded to commonly known narratives from literature or poetry but I can’t imagine someone getting any kind of story out of Jackson Pollok’s Full Fathom Five (the title refers to a poem from Shakespeare’s The Tempest).

I will discuss Six methods of relating narrative through art. My contemporary examples will all be works done in clay but for the sake of clarity in explaining my ideas I will also refer to paintings that exemplify the narrative methods that I discuss. I don’t generally care for artificial categories in ceramics. In the case of narrative ceramics, though, it is useful to break down the methods of telling stories into categories so that we can clearly describe the connection between technique and meaning. It also provides a much needed foundation upon which we can build a good dialogue about narrative clay. These categories are as follows.

1. Continuous narrative: A piece wherein multiple events in the same story line are present on the same space. This was common in early Renaissance painting but faded away over time. There is often a somewhat linear progression in the flow of events in a continuous narrative piece, but to a person who is accustomed to the more common and simplified structures that are common today it can be hard to read these pieces.

2. Multiple panel narrative: A piece composed of a group of sections organized chronologically wherein each part shows a single event in a story (like a comic strip). These kinds of pieces are common in chapels and cathedrals and are often helped along with text. This brings us to our next category…

3. Text dependent narrative: An image or group of images that work together with text in order to tell a story. Generally a text dependent piece is one that leaves out large parts of the story which are filled in by the text.

4. Referential narrative: A piece that portrays a moment in time from a well known story. Because the viewer is expected to know the narrative before hand the image acts as a prompt and the rest of the story gets filled in by the viewer.

5. Implied narrative: An image that clearly indicates what happened before and what will likely happen next so that the narrative is implied by a single moment.

6. Free Narrative: A piece that uses imagery in a way that does not tell a specific or recognizable story, but provokes the viewer into creating a narrative from the given visual information. The specific details of the narrative will vary from viewer to viewer. *This may or may not qualify as narrative, but I include it as food for thought and discussion.

These categories are not necessarily the final word in defining narrative ceramics, but they serve as a structure through which we can discuss it. It is common for the different methods to be used in combination with each other (for example an artist may use text along with multiple panels to tell a story). Because the artists who create narrative works are not concerned with staying within the parameters of artificially defined categories the lines that separate them are often blurred, this is especially true among contemporary artists

Continuous Narrative

Continuous narrative is interesting because it shows events that would more commonly follow an orderly timeline but are all simultaneously present in one piece. This takes a narrative that would otherwise be chronological and makes it synchronic. Scenes from the Passion by Hans Memling, is a good example of continuous narrative in Renaissance painting. In the piece we see scenes from the New Testament’s account of the last days of Jesus’ life. Jesus appears entering Jerusalem in the upper left hand corner and then going through various actions surrounding the crucifixion as recounted in the Bible until in the lower right hand corner he appears as the resurrected being. I count Jesus appearing eighteen times in the painting. There are two Golgotha crucifixion scenes and three tombs all present in a stylized Jerusalem. In the context of a Christian themed painting the ability to see all events simultaneously may refer to the doctrine of godly omnipresence.

In contemporary ceramics there are some interesting examples of works that use continuous narrative. In some cases artists take advantage of the fact that a vessel form can be viewed from various angles to represent more than one event in a narrative on a single piece without dividing it into sections. A simple example of this is Cindy Kolodziejski’s To and Fro. On one side of the piece is an image of a bald headed old man swinging at a playground. He is wearing a dark business suit, a pair of glasses and a child like grin on his face. On the opposite side of the piece the same character is shown from behind on the backward pivot of the swings pendulous action. In this case the synchronic nature of this continuous narrative contributes to the meaning of the piece. The man is moving but never going anywhere new in his continuous and timeless play. His clothing suggests that the piece is being allegorical rather that literal. The swing symbolically represents the trajectory of his life’s work. He is only interested in childishly gratifying his misguided desires. His greed and selfishness know no end because they are inverted like two mirrors facing each other; desire wanting desire and so on forever. A self serving business man who, by his appearance, could wield a great deal of power will cause a lot of trouble. Another clue illuminates the darker meaning of the piece. The vase is Victorian in form which in contemporary ceramics generally calls to mind an era of imperialist oppression. This never ending motion that is no more than an illusion of progress for the eternally self serving business man is a harsh criticism on the oppressive nature of capitalism in a male centered society. It encourages contemplation and lays a moral imperative at the feet of those who understand.

Multiple panel narrative

An example of multiple panel narrative structure that follows a more traditional order is the painting entitled Scenes from the Life of Christ by Renaissance artist Gaudenzio Ferrari. The piece essentially reads like a graphic novel, starting at the top you follow each panel from left to right until you reach the bottom. One interesting manipulation of the structure that the artist employs is a section near the center that uses a box that is four times the size of the others. This larger section holds an image of the crucifixion. Its size is there to act as a means of emphasizing the importance of the moment being depicted. In Renaissance art multiple panel narrative structure essentially displaced the use of continuous narrative. The change indicates a trend toward neat, logical structuring that was easy to read. This affinity for logic and structure is likely the same compulsion that motivated the developments in composition, representation and perspective that can be observed in Renaissance art.

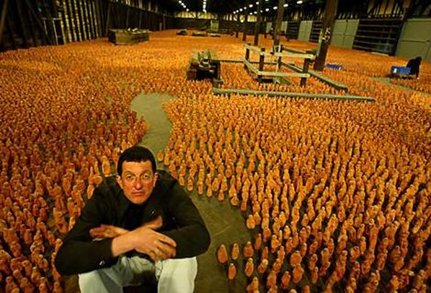

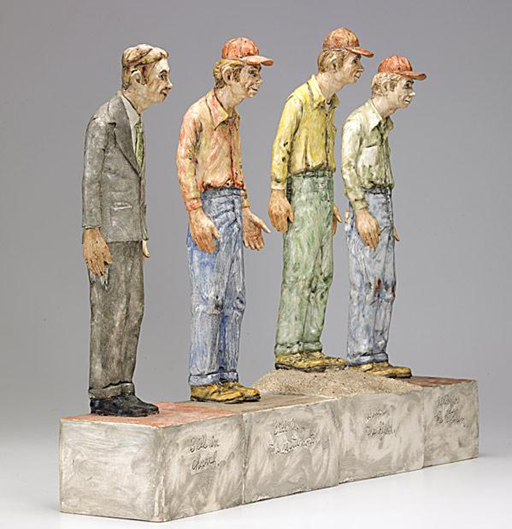

For the contemporary ceramic artist Jack Earl his character Bill is often sculpted multiple times as a kind of multiple panel story. For Earl Bill is a way of discussing identity and morality. Over time Bill is shown in a number of attitudes. In This is Bill. This is Bill Thinkin! This is Bill Talkin! This is Bill Tryin to Rest. This is Bill Workin! , Bill is represented in the attitude of thinking, talking, resting, and working as the title pointed out. In a lot of the Bill pieces you don’t catch more than a wry sense of humor, but as you look at the body of work it begins to become clear that Bill represents an ideal. He is unpretentious, and sometimes a little silly, but always an example of a kind of morality that the artist is drawn to. Two more representations of Bill are placed side by side in another piece called Bill in the Light and Bill in the Dark . In this piece the passage of time is alluded to as one of the Bills is painted black as though he were in the dark, while in the other likeness Bill is painted in full color as though he were standing in broad daylight. In other pieces Bill is shown in the field, the pig pen or at church. Bill’s facial expressions and mannerisms don’t change much in these pieces. The only difference is in superficial elements like clothing or tools. Bill is stable and predictable; he has a simple kind of righteousness that Earl wants to represent as the character goes about his daily duties. Bill is a composite of a combination of the artist and his father in law Roy. In one piece Jack Earl leaves the pseudonym out and calls “Bill” by his true name, Roy, in a piece entitled Roy, the man who saved his family. Acts, Chapter 16, Verse 31. (1984). In this piece the artist uses text in the title as a narrative device. This is something that the artist has done quite a bit throughout his charier.

Text dependent

Let’s keep looking at Jack Earl’s work. He has taken the narrative capabilities of a title to the extreme. The language in these titles is purposely written in the vernacular of rural Ohio to add to the work’s sense of place and implicit good ol’ boy morality. One such piece is a sculpture of Bill/ Roy with a carrot growing in the place of an index finger. The title of this piece creates an entire myth to accompany the figure :

The story of Carrot Finger: I knew a guy who had a carrot for a finger. I guess he had it when he was born cause he had it when I met him in high school when we was boys. It was just a carrot stickin’ out where a finger ought to have been. When I first noticed it I looked out of the corner of my eye at it a few times and then got used to it and didn’t pay any attention. Nobody else did either, they were all used to it. Sometimes some younger kid would holler ‘Carrot Finger’ at him from a distance but he didn’t pay any attention to them kids. When he got older and went to church, a wedding or a funeral, he would keep his carrot finger in a pocket so he wouldn’t distract from the service. He got married to a local girl here, a real nice girl, but not as pretty a one as he could have got, I suppose, if he hadn’t had a carrot for a finger. They had three kids and they all come out normal. Anyhow, one time he was walkin in the woods. It was in December, one of those special days in December when the sun is real warm and little fluffy white clouds was pasin shadows over you once in a while. He had plenty of clothes on since it was December and it was nice and warm and he layed down in the grass on the side of that hill and he was watchin’ the clouds pass by and listnin to the bees buzz. You know how nice it is to hear bees on a real warm winter day. Well he was layin there and he went to sleep but what he didn’t know was that there was a lot of rabbits in that woods. When he woke up his finger, the carrot one, was gone. He told me he thought it might grow back but it didn’t.

Yes, that whole thing is the tittle of the piece. Earl wrote his carrot finger story on a plaque that accompanies the piece.

Referential Narrative

Referential narrative generally does less actual story telling than the other groups because the artist assumes that the viewer will already have a certain depth of knowledge about the subject. Because of this, referential pieces often focus more upon other issues. This is the case in Caravaggio’s Crucifixion of St. Peter. Caravaggio’s dramatic use of light and composition pared with his skill in representation create an arduous depiction of a moment in the death of Peter. The dynamic composition is filled with diagonal lines and bodies in strenuous motion as they hoist Peter to be hung upside down. Our perspective is close, cutting out all peripheral action. This has the effect of drawing us into the composition and the painful moment that it represents. This is a motif that had already appeared in public art a number of times before, and viewers were assumed to have knowledge of the story from which only a brief snap shot was depicted. Because Caravaggio didn’t need to concern himself with telling the whole story he could focus on the formal and emotional elements of the composition.

In Kurt Weiser’s Europa a gourd shaped ceramic form is held at a tilt by a curved metal bar that allows it to turn like a globe. On the piece is a detailed china paint illustration of a moment in the Greek myth of Europa. In the story the princess Europa is abducted by Zeus who disguised himself as a tame bull. The bull wins the princes’ affection and when she decides to try to ride him he takes her down to the ocean and swims to Crete. Zeus reveals his true self to her there and, among other things, makes her the first Queen of Crete. On the piece there is only an image of Europa riding a bull in the water, but it is not hard for a person who is familiar with the narrative to fill in the rest.

Implied Narrative

Magdalene Gluszek uses the shape shifting nature of symbolism to encourage contemplation of desire and inhibitions in her piece Ate the Cake. At face value the narrative is basically this: a little lizard headed girl wanted a piece of cake really bad. She loved cake so much that she wore a pink dress decorated with little red cupcakes. She got a piece of cake and ate it quickly, getting frosting all over her face. The moment in the narrative that is depicted by the artist shows the elation that lingers while the lizard girl is still chewing the last bite. She is pigeon toed, full figured and uninhibited. She claps for joy looking up, maybe at the next piece of cake that has become the new object of her desire now that the last piece has no more pleasure to give. The little girl’s attraction to pleasure is unreserved; her primal state is made clear by her animal head. Children will go to any length to get their hands on a little junk food, and they will throw fits if they are denied it. In this piece the cake, the child’s candidly expressed desire, and her momentary pleasure in gratifying that desire are symbolic of the numerous ways in which all humans experience these same emotions. The piece reminds us that desire and the objects of want are too often the primal demiurges that drive our species. In our weaker moments we can often be animals whose behaviors are driven by desire. We become more adept at disguising this as adults, but this changes little. On the surface Ate the Cake is a simple narrative but as you decode it’s symbolism its meaning is as numerous as are the objects of our desires and the things we do to get them.

Meaning is slippery. This is a fact that we have become increasingly aware of. Language is not exact and signs and symbols seem to lose their effectiveness to communicate clearly as they gather more and more meaning over time. Artists today will often play with the multiplicity of possible interpretations that are imbedded in our means of communication It’s meaning at any moment is established by context and viewer. These pieces are objects of contemplation rather than a final word on a given subject. Their possible meanings only increase over time. This kind of fragmentation in meaning is important in the aims of the postmodern agenda because it makes room for more than one point of view, and ultimately for peaceful cohabitation. If meaning is not absolute and significance is determined by context then it is hard to accuse someone of being wrong.

These ideas inspire the last category of narrative:

Free Narrative:

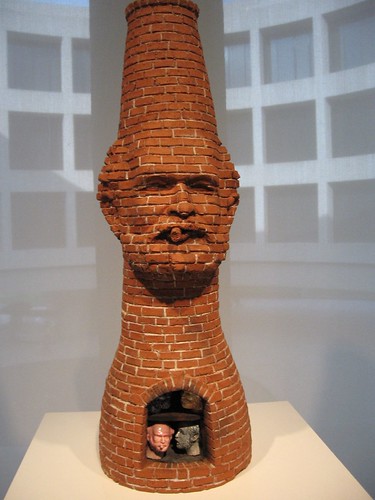

Dada Thrown by John DeFazio(this is the piece that we looked at in class) is a good example of free narrative because it is full if images that are loaded with meaning and a viewer could potentially construct any number of stories from them. Inevitably though, the stories that are derived from the piece will not be the same for each viewer. In fact some(maybe most) viewers will not feel inclined to create a narrative from the piece at all. Hence the question: is this narrative art? Does a piece’s potential to inspire someone to construct a narrative make it a piece of narrative art? I’m not inclined to say one way or the other. There does need to be a point though where an image based art piece can no longer be called narrative. This doesn’t mean the piece is not good or that it is unsuccessful as a piece of art. It just isn’t telling a coherent story.

.jpg&t=1)

Shiro Tsujimura

Shiro Tsujimura